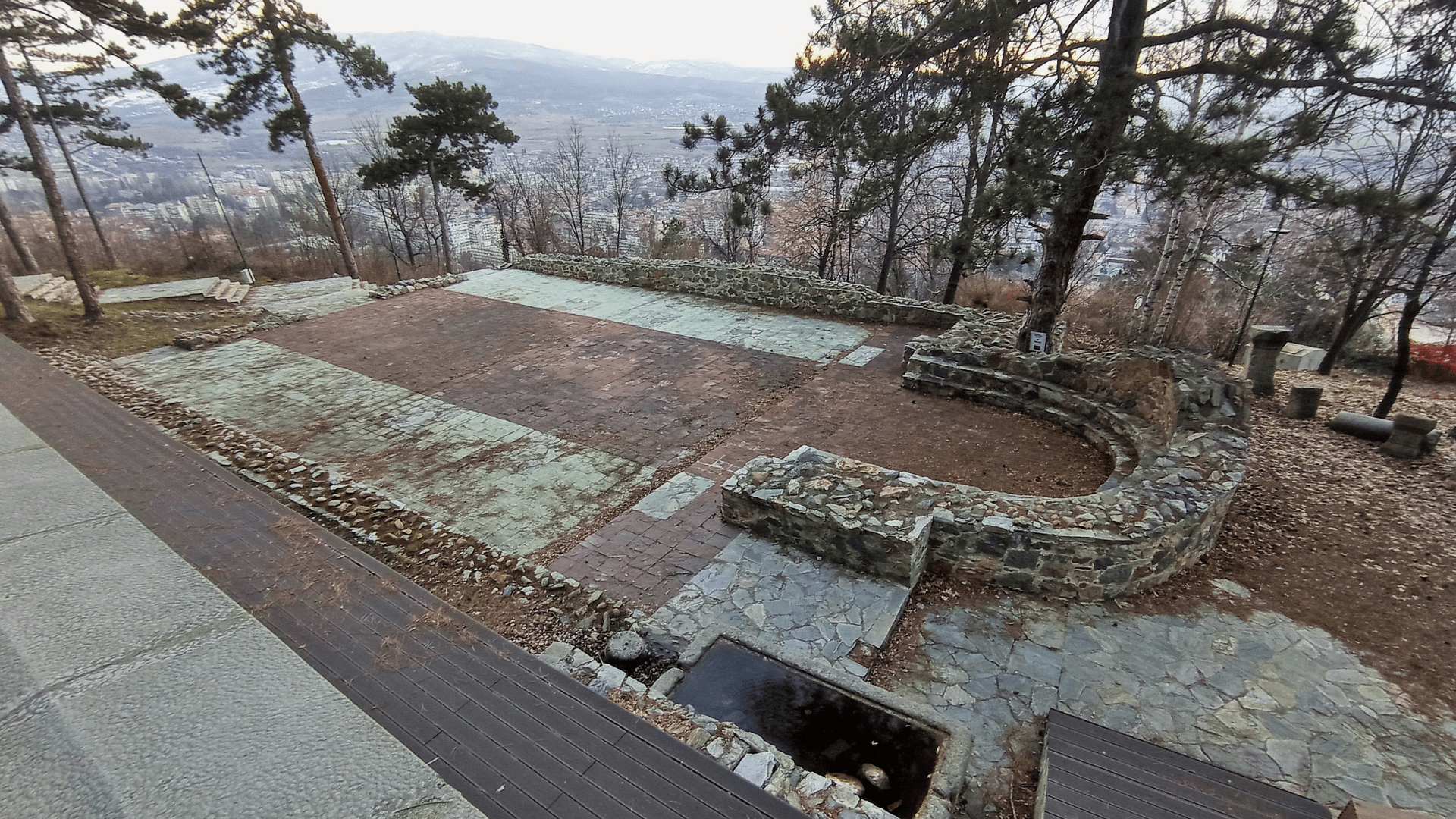

Archaeologists working in the ancient town of Spello, Italy uncovered a remarkable discovery during their recent excavation efforts.

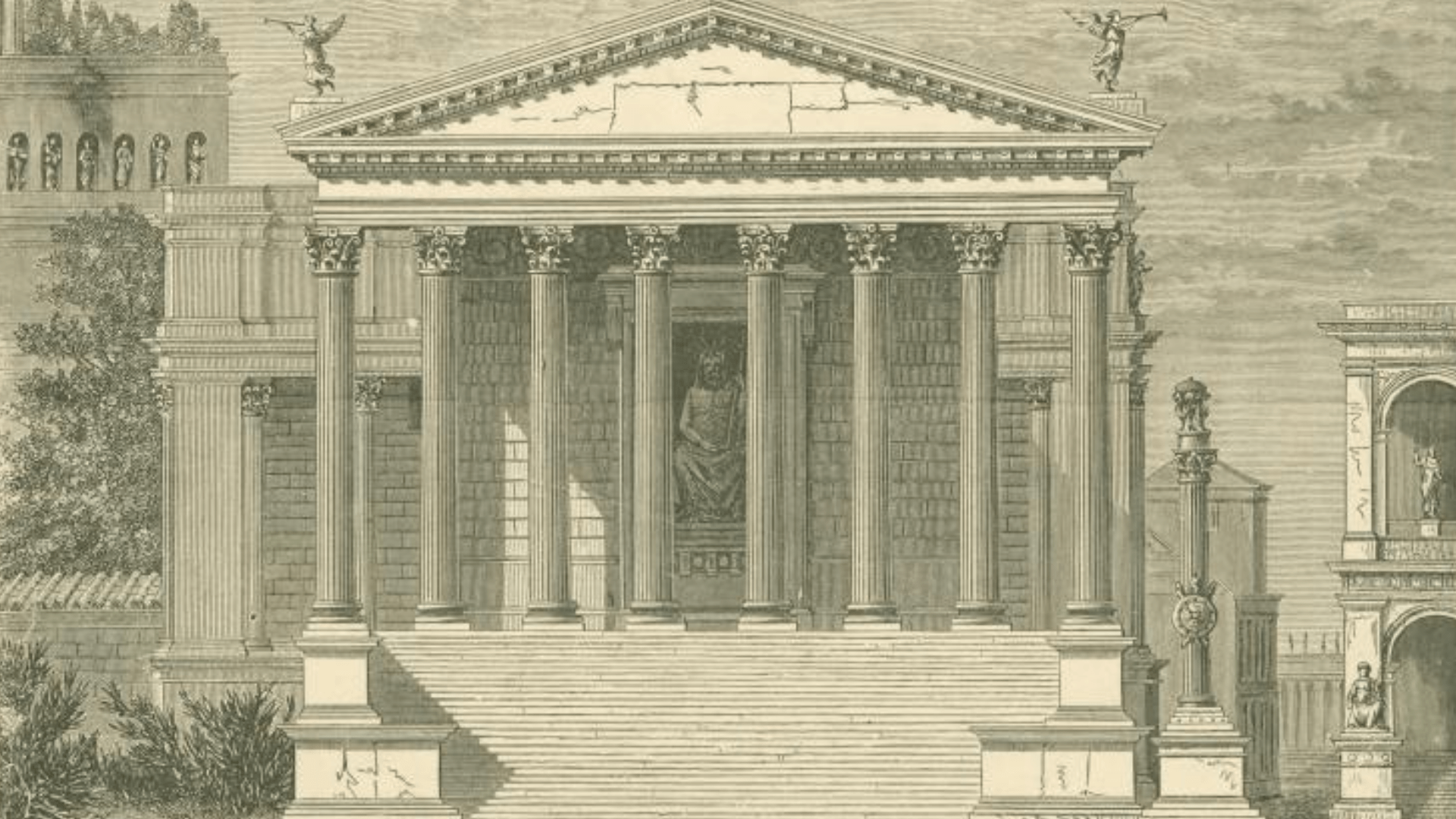

What they unearthed was an ancient pagan temple dating to the Roman period. They believe that the building was constructed during the reign of Emperor Constantine, Rome’s ruler from 306 to 337 C.E.

Who Was Constantine?

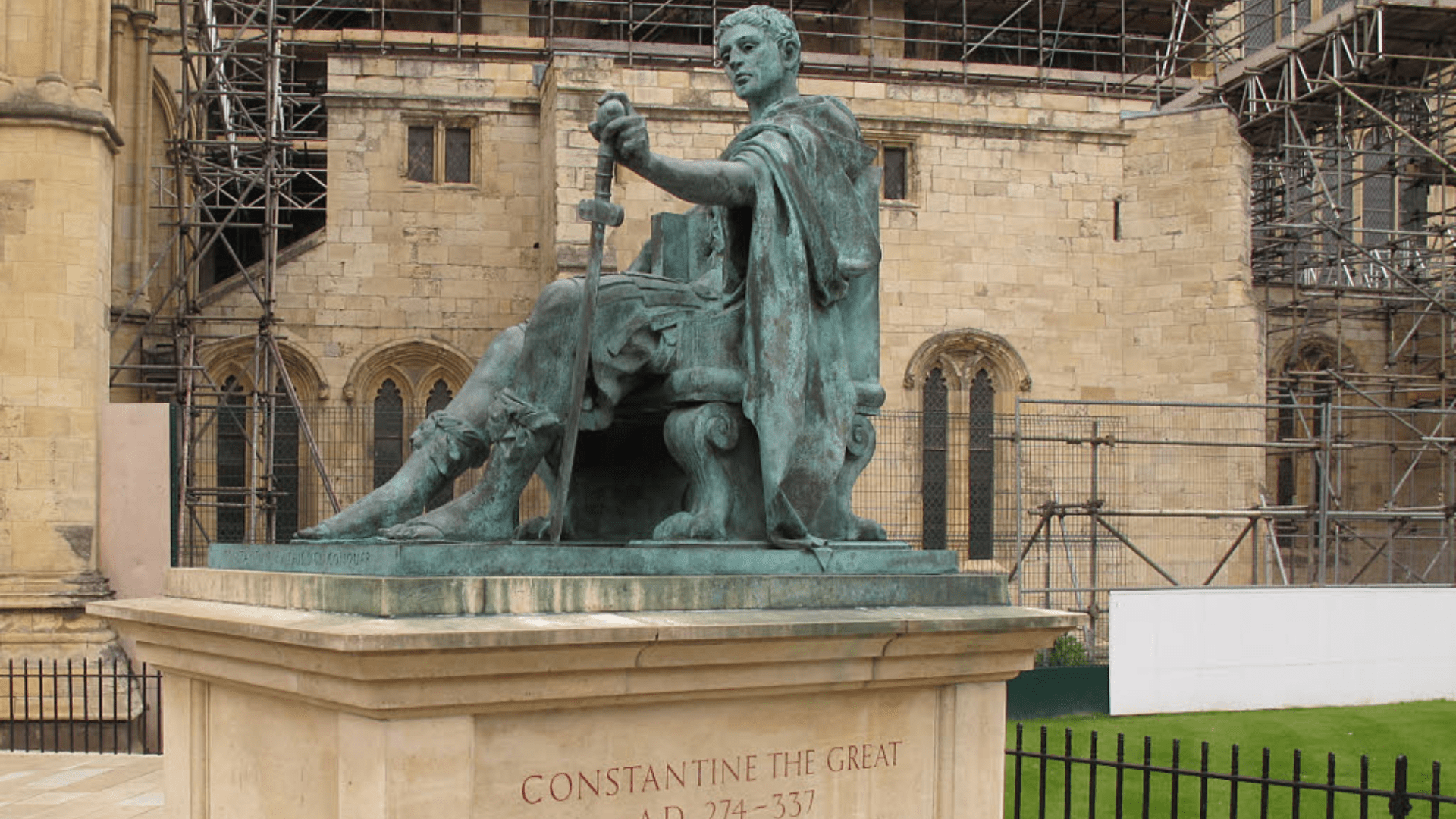

Constantine I, or Constantine the Great, was a Roman Emperor who ruled in the first third of the 4th century C.E.

He is remembered for his leadership during a major time of transition in the Roman Empire, as well as for moving the capital of the empire to Byzantium, later rechristened Constantinople. But he is perhaps best known as the first Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity.

The Roman Pagans

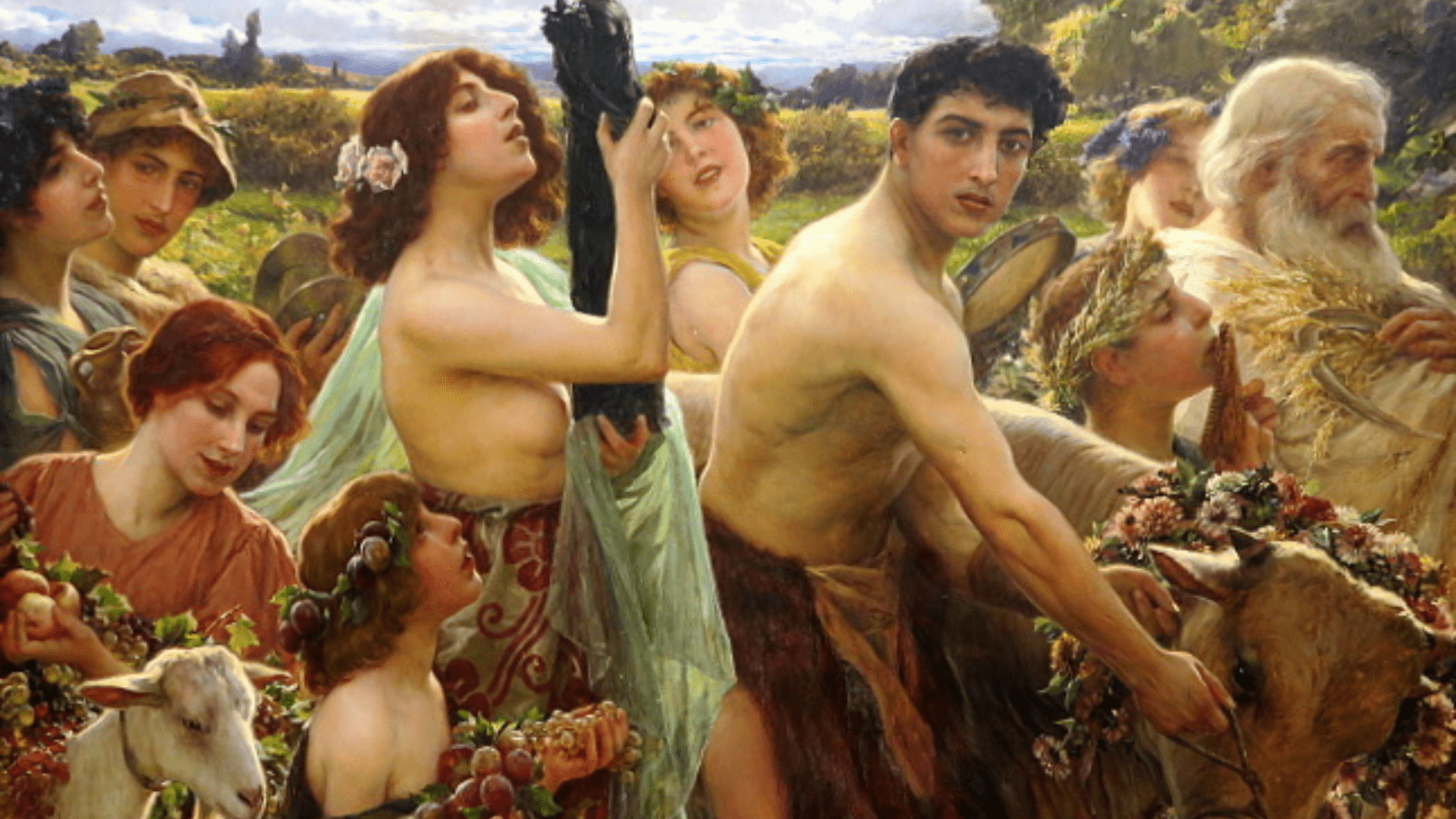

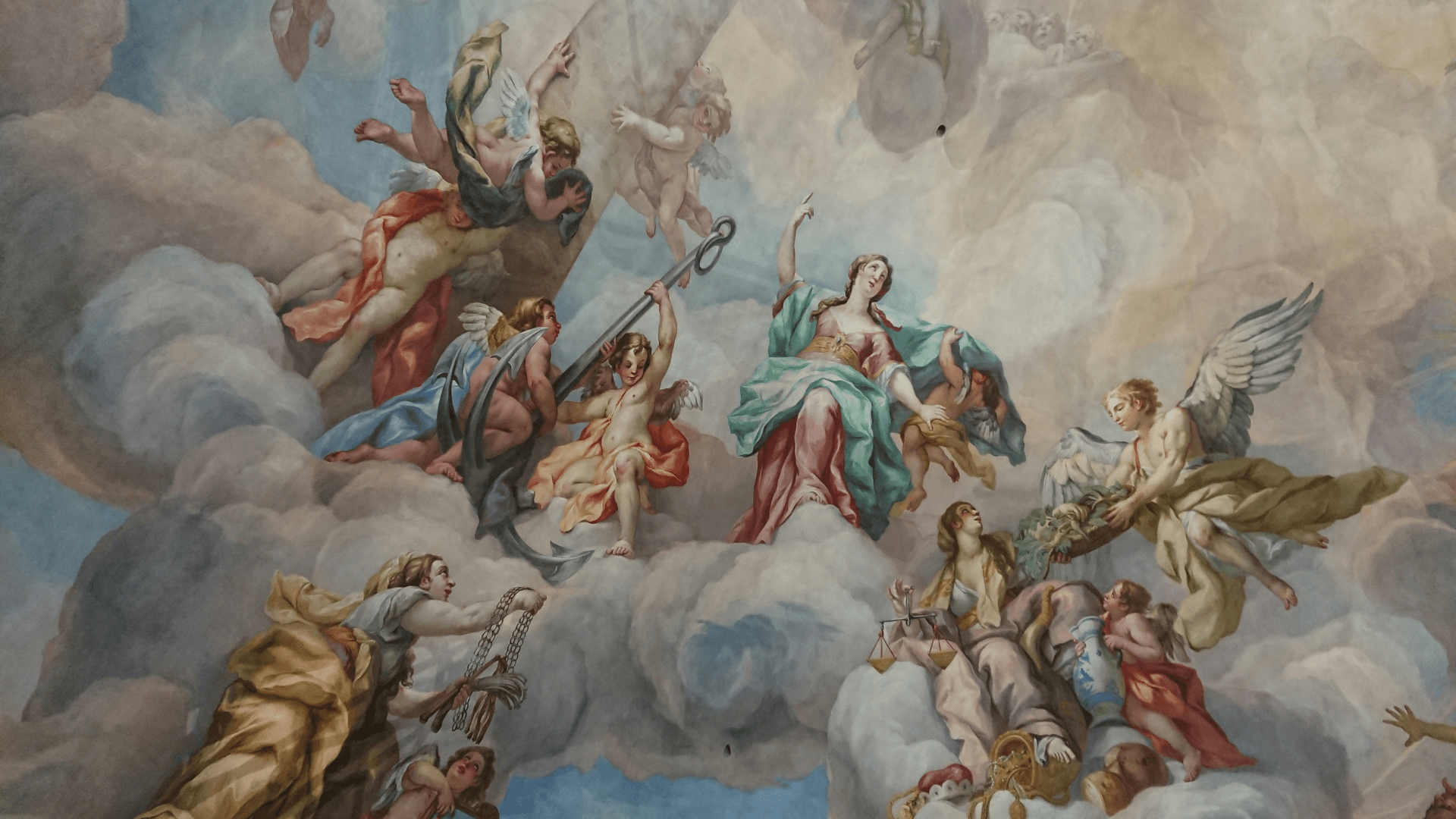

The Roman Empire was a thoroughly pagan institution from its inception. The Romans worshipped many gods and supernatural beings who were generally linked to the natural world in some way.

Christianity, though now a major world religion, was a peculiar phenomenon for the Romans, and the early Christians were heavily persecuted. When Constantine converted, however, the Roman Empire gradually adopted more and more elements of Christianity. At least, that’s how the popular story goes.

Did Constantine Make Christianity the Official Religion of Rome?

There’s a popular story that neatly condenses history and says that Constantine changed the official religion of Rome to Christianity.

However, the new archaeological findings at Spello attest to the fact that this is an inaccurate version of reality. Researchers stated in a press release that the uncovered temple “shows the continuities between the classical pagan world and early Christian Roman world that often get blurred out or written out of the sweeping historical narratives.”

The Inspiration for the Archaeological Dig

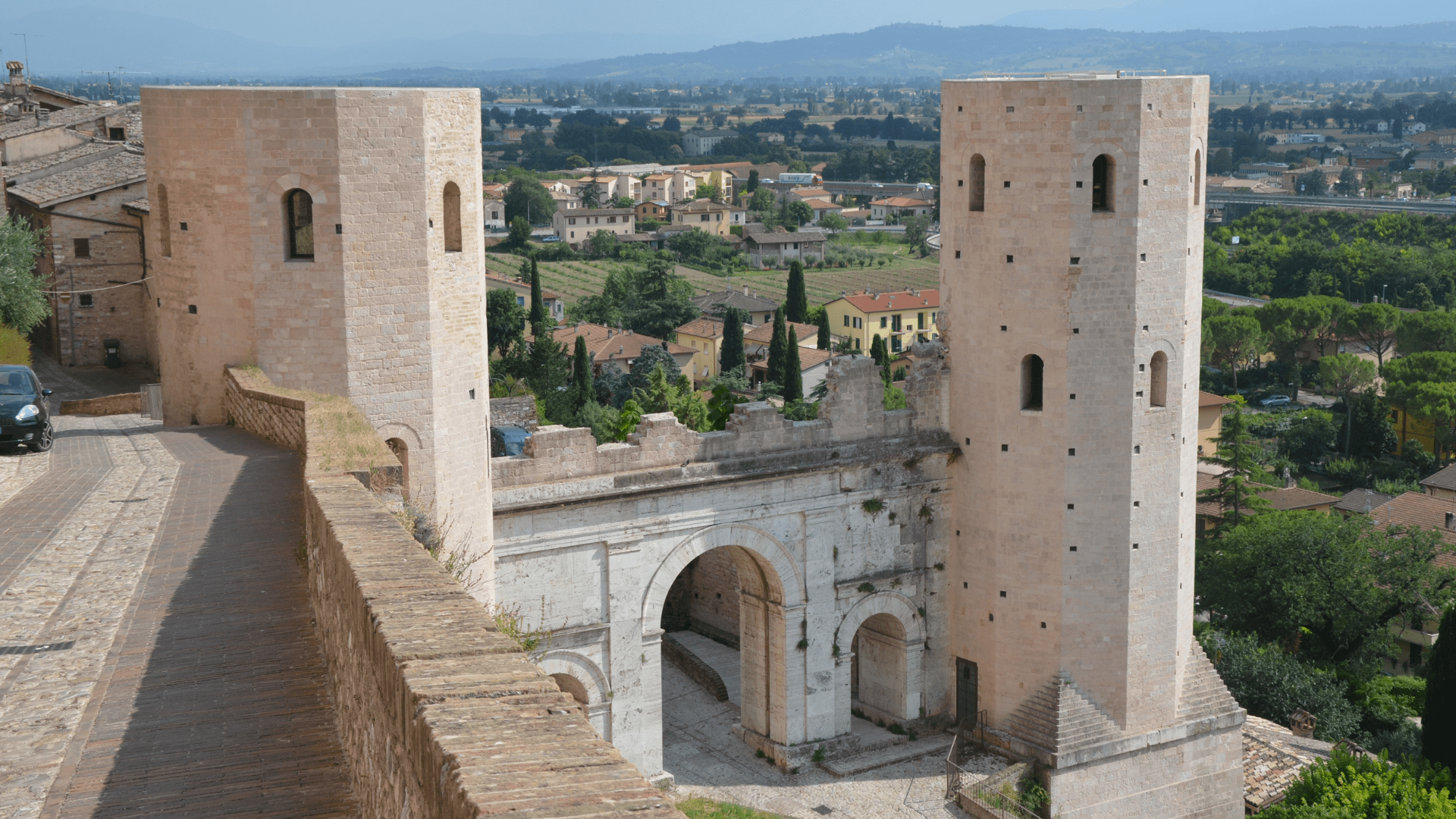

The decision to begin an excavation at the site in Spello was sparked by an ancient inscription that hangs in the town hall.

The inscription was originally recovered in the 1700s. It states, in language directed to the townspeople of its time, that the creation of the temple constituted a massive undertaking. What intrigued researchers was that it also grants the town inhabitants the ability to celebrate a religious festival in Spello instead of making a long journey elsewhere.

The Condition for Festival Celebration in Spello

The inscription, however, contains a condition for townsfolk who wished to celebrate the religious festival within Spello.

Constantine stipulated that the citizens must build a temple dedicated to his ancestral worship. Specifically, the temple would serve as a place for worship of the Flavian family, Constantine’s own predecessors.

Why Would Constantine Want People to Worship His Ancestors?

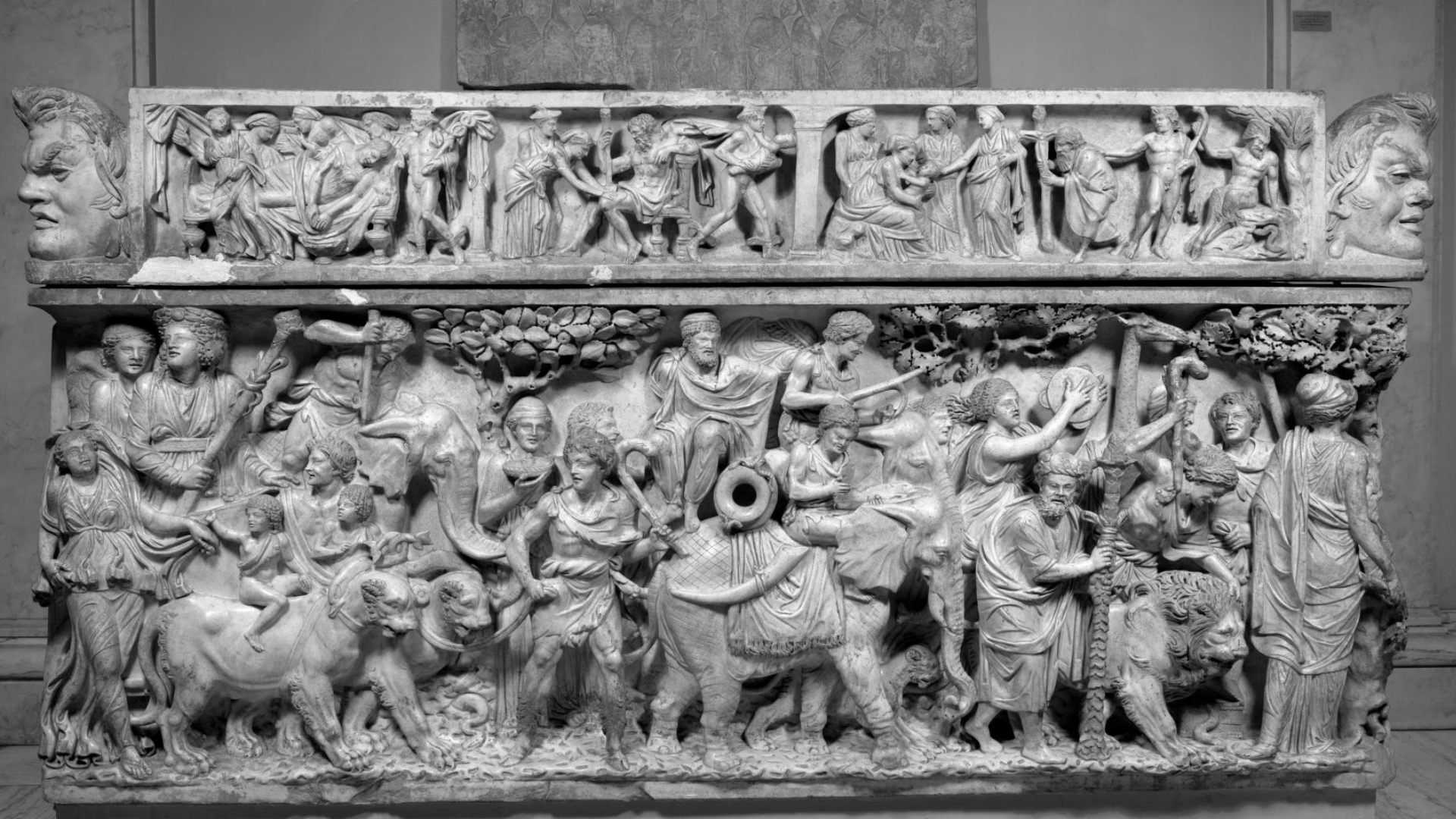

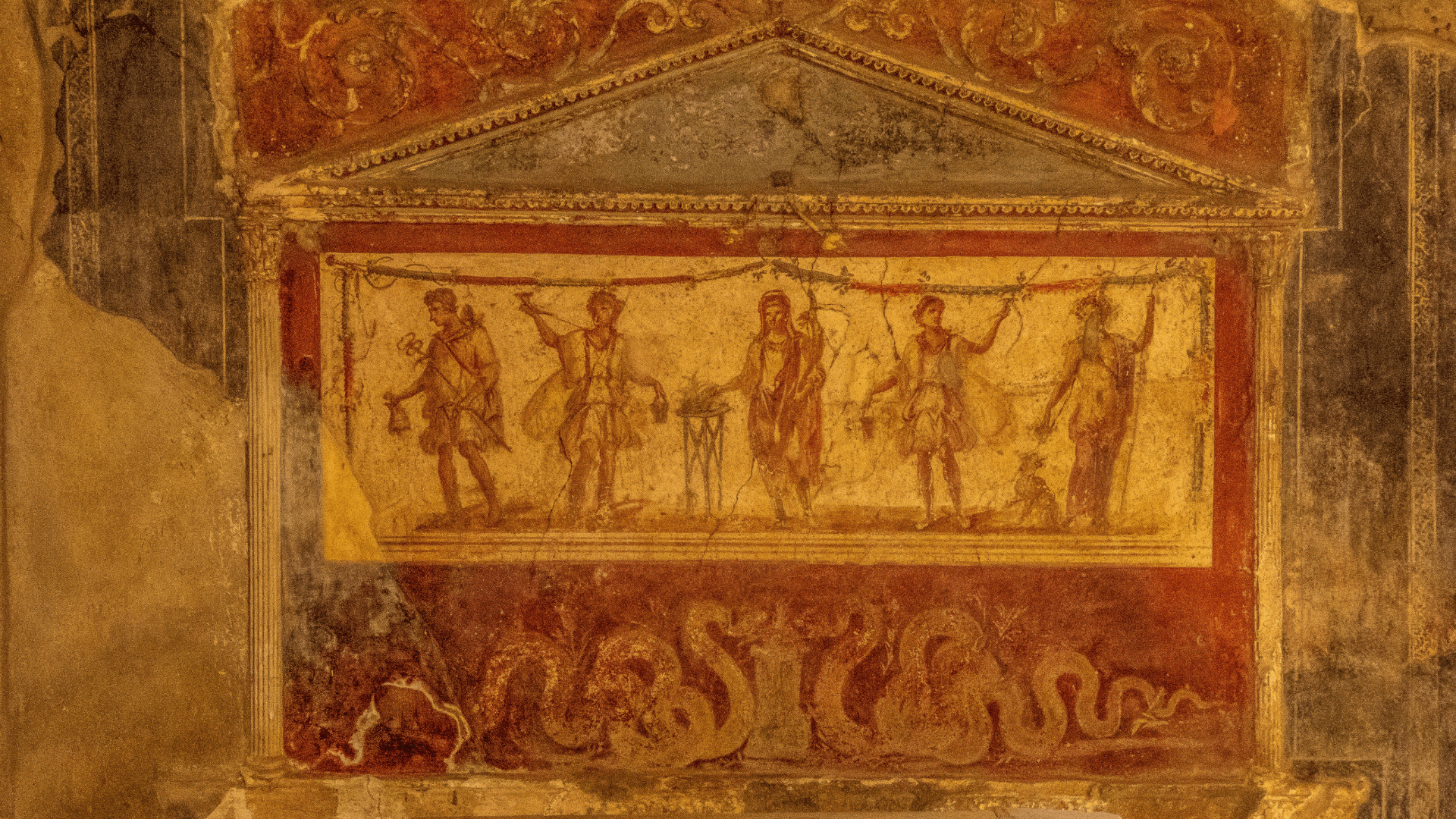

This condition that Constantine decreed stems from a centuries-long belief of the Roman people and rulers, known as the Roman imperial cult.

Romans believed that the emperors and certain members of their families were imbued with divinity, and thus required that citizens worship them as divine entities.

The Social Impact of Ancestor Worship

Was there more to the Roman imperial cult than an intriguing flourish of self-aggrandizement by emperors and their families? It seems that there were actually significant social consequences of this religious activity.

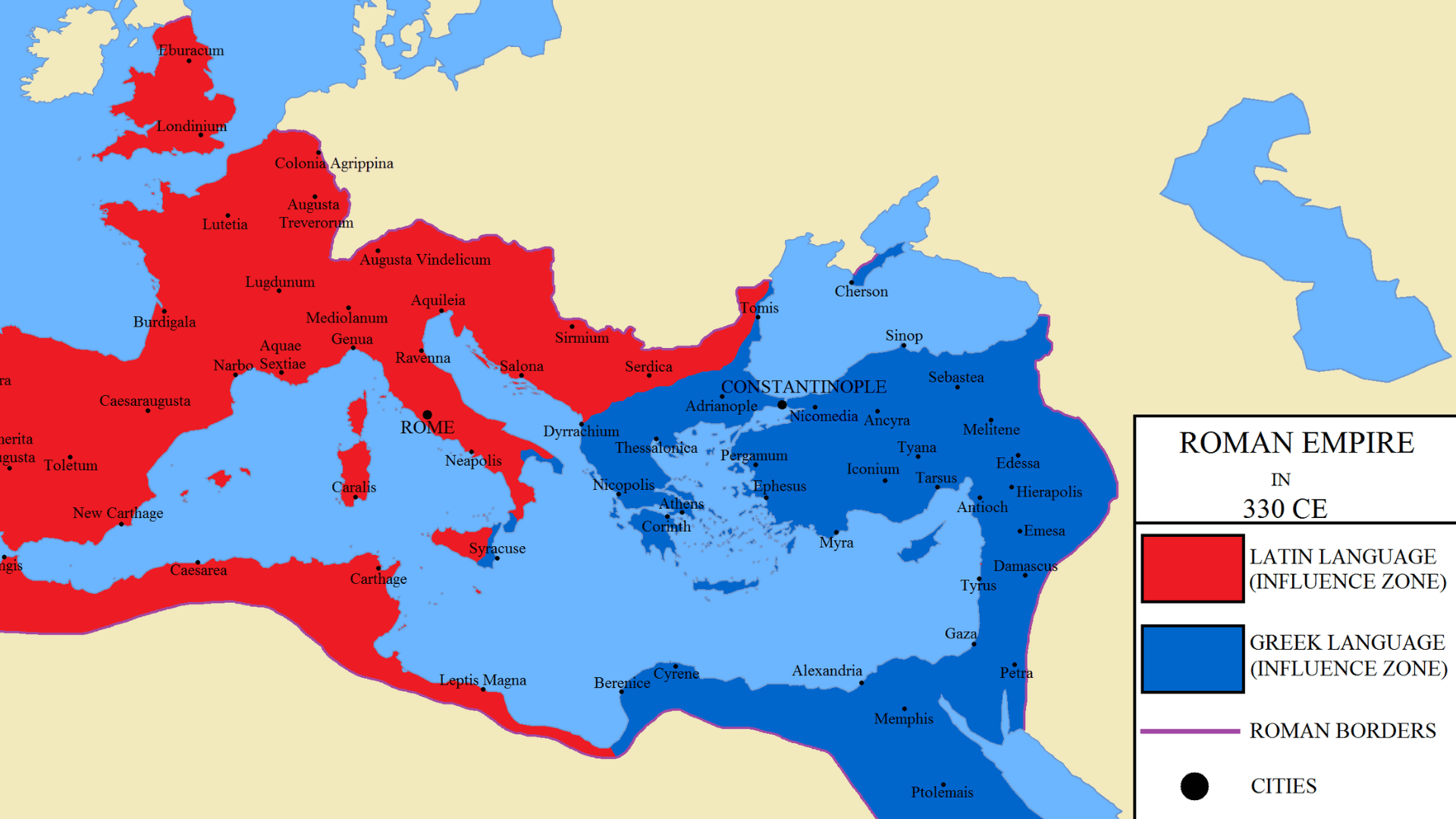

The Roman Empire was massive. It spanned three continents, its citizens spoke multiple languages, and there was innumerable local traditions spred across its vast expanses. The Roman imperial cult was a universal glue for the Roman public, which helped unite them around a similar tradition and ideals.

Pagan Worship at Spello

This particular temple’s existence was suspected for many years by scholars, but its recent recovery helps shed light on a specific period of transition in the Roman Empire.

This temple was likely used as a place of pagan worship and religious activities for at least two generations following its construction, when paganism would be officially outlawed by emperor Theodosius in 392 C.E.

Paganism and Christianity in Transition

This archaeological excavation serves as another piece of evidence for the existence of a transitionary religious period in the Roman Empire, a time when paganism and Christianity blurred together.

It might be well-known among scholars that Christianity didn’t overtake paganism overnight, but this discovery at Spello serves as a reminder to everyone of this fact. This temple shows quite clearly, with tangible evidence, that paganism existed in tandem with Christianity for a significant period of time in ancient history.

How This Temple Changes Things

As mentioned above, scholars have long known that there is no clear distinction between the end of paganism and the beginning of Christianity. However, this specific temple is still quite significant.

While evidence has been recovered to support pagan worship in the 4th century, and evidence likewise shows Christian support of the imperial cult, this temple is the first major discovery that cleanly bridges the gap between those two things.

The Path From Paganism to Christianity

This excavation further shows how non-linear the path from paganism to Christianity was in the ancient world.

There were many detours and plenty of unlikely cultural mixtures that took place. It is a testament to how both pagan and Roman Christians blended patriotism, the imperial cult, and other forms of worship into their own brans of religious practice.

What Was Early Christianity Like in Rome?

Christianity was viewed initially as a Jewish Sect. Early Christians in Jerusalem kept the Sabbath along with other Jewish customs.

Christianity spread fast in Rome among the lower classes in part because it established a community of equals in faith.

How did Christianity Spread in Rome?

In part, because “all roads led” there. Rome’s extensive road system allowed for the message to spread far and wide.

Additionally, the faith was easy to adopt for a variety of reasons. There is no denying however that trade and trade routes played a significant role.

What Do We Know About Early Roman Faith?

Romans were polytheistic, with Gods and rituals aligned to almost everything. The major early influence was Greek religion and Greek Gods.

Rome however spun things into it’s own unique direction, including it’s own origin story as part of it’s faith, with the twins Romulus and Remus being sons of Mars, the God of War. Politics and culture were intertwined deeply with various forms of faith.

Did Romans Feed Christians to Lions?

Sadly, yes. Damnatio ad bestias, or ‘Condemnation to beasts” was a form of capital punishment and entertainment in 2nd Century Rome.

Runaway slaves, criminals, and Christians were all condemned to the beasts, as it were, in the Flavian Amphitheater. Prior to this Emperor Nero had clothed Christians in animal skins and fed them to wild dogs.

What Role Did Faith Play in Rome’s Fall?

There are many reasons Rome finally fell, but there is no doubt the rise of Christianity played some small role. How exactly?

The destabilization of the underpinning faith tied to national pride eroded some of the core Roman values and beliefs. It at least weakened the general spine of Roman culture allowing the people to drift apart after centuries of unity across a massive expanse.

The Melding of Paganism and Christianity

The success of the Catholic church in medieval Europe was a long process that began far back in pre-Roman, pagan times. However, the Roman Empire’s vast interconnectedness greatly improved the church’s ability to spread its message.

The discoveries at Spello show us that there was a clear period of transition between paganism and Christianity. However, this transition really took on a much more prolonged form, which we can take a look at now. This slow evolution might be most easily seen in the development of Halloween.

What Are the Origins of Halloween?

The Halloween bash we know in the U.S. is like a remix of different traditions and parties: there’s the Celtic shindig called Samhain, a dash of the Roman party for Pomona, some early Catholic Church vibes, a hint of the Protestant Reformation, and even a pinch of Guy Fawkes Day.

Why Summer and Winter Solstice Are Important

The Celtic tribes were the early inhabitants of the United Kingdom, Ireland, northern France, and Brittany, establishing their presence long before the era of Christ. Guided by pagan beliefs, these communities structured their existence around hunting, herding, and the observance of seasonal phenomena.

Of particular significance were the onset of summer and winter, critical junctures dictating whether herds required shelter or open pastures. In essence, the meticulous handling of these seasonal shifts defined the Celtic approach to nurturing a primary food source, underscoring its pivotal role in ensuring the very survival of these ancient peoples.

What Is Samhain?

As winter commenced, constrained by spatial limitations, only the prime members of the herd found refuge within shelters; the remainder faced inevitable slaughter. This culling of livestock marked a ceremonial occasion filled with revelry and feasting, dedicated to Samhain, the esteemed Celtic Lord of the Dead.

The Celtic Otherworld

During Samhain, revered ancient burial mounds, seen as portals to the Otherworld, were ceremonially opened, creating a mystical link between the living Celts, their ancestors, and the supernatural. On this eve, the Celts believed ghosts and malevolent entities emerged, causing havoc in the countryside, damaging crops and unsettling homes.

The Druids highly valued this night for witchcraft and divination. Samhain, the Lord of the Dead, convened lost souls for reevaluation, prompting tributes from the Celts to influence his judgment and improve the fate of their departed loved ones. Offerings of food and wine were also made to fortify ancestors’ souls during their journey to and from the Otherworld.

Where Costumes Came From

Communities collectively engaged in the ritual, with members donning masks and parading through villages, strategically deceiving spirits and diverting them away from populated areas. Occasionally, Celts enticed spirits with desserts as a symbolic offering to hasten their departure from the vicinity.

The Roman Festival of Pomona

Pomona, a Roman goddess embodying orchards and harvest, derived her name from the Latin “pomum,” meaning “fruit.” The ancient Romans marked her celebration on November 1st with feasts showcasing nuts, apples, grapes, and other orchard fruits.

In mythology, Pomona, a woodland nymph, was pursued by various rustic divinities, including Vertumnus, the god of seasons. After multiple disguises failed, Vertumnus, adopting the guise of an old woman, revealed a heartfelt prophecy of love, ultimately winning Pomona’s affection.

The Romans and Celts Intermix

The Romans observed Pomona’s festival on November 1, marking the end of the harvest. By the first century A.D., Roman and Celtic lives intertwined due to colonization, fostering a shared existence in small villages across Europe and the British Isles.

Pomona’s celebration aligning with Samhain on the calendar, coupled with the proximity of Roman and Celtic daily life, naturally fused the two festivities. This amalgamation persisted, influencing modern Halloween practices, with the Roman orchard harvest linking to apple-centric Halloween traditions. The encounter with Christianity in the first century A.D. resulted in a synthesis of pagan traditions with the early Catholic Church.

Early Catholic Church Customs

Christianity, initially a marginalized and persecuted belief system, underwent a remarkable transformation into a global religion from the first to the fourth centuries.

The legalization of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire by emperors Constantine and Licinius in 313 marked a pivotal moment. By the close of the fourth century, the early Catholic Church boasted a significant following, with an estimated 30 million adherents.

Early Christianity Succeeds!

Christianity’s triumph can be attributed, in part, to its tapping into an unrecognized need. In contrast to pagan traditions centered around gods intertwined with daily life, nature, and human welfare, Christianity catalyzed a profound shift. Beyond a mere shift from pantheism to monotheism, it fostered a religious focus on eternity.

Early Christians instilled a need for salvation, practicing to escape eternal torment and gain everlasting reward. By the fourth century’s close, millions of pagans were converted. The success also stemmed from Church leaders’ strategic approach—assimilating, not eradicating, pagan rituals. This gradual transition integrated Samhain and Pomona festivals into All Saints’ and All Souls’ feasts.

All Saints’ Day

Originally observed on May 13, All Saints’ Day commemorated early Christians dying for their faith without acknowledgment. Pope Gregory III shifted it to November 1 in the eighth century, strategically aligning it with Samhain and Pomona’s festival to absorb pagan celebrations.

Initially dedicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs, Pope Gregory IV expanded it to encompass all saints. To replace pagan offerings, the Church endorsed “soul cakes,” given to the poor in exchange for prayers. A growing practice, it led to “souling” songs and door-to-door visits for ale and money. The Church also introduced the All Saints’ masquerade, where churches displayed relics or, in poor churches’ case, the congregation dressed as saints, angels, and devils—a Christianized version of pagan parades.

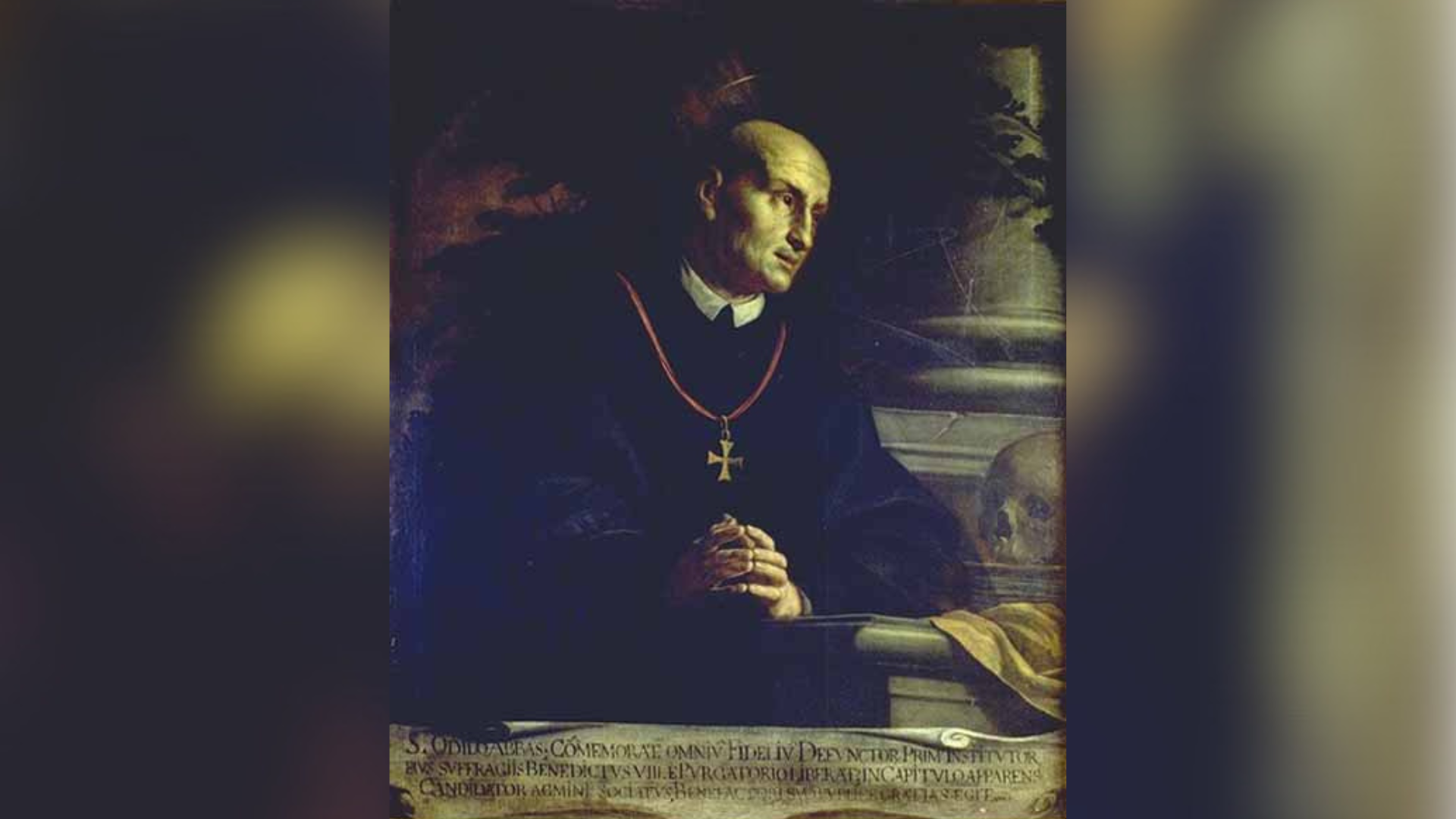

All Souls’ Day, first proposed by Saint Odilo of Cluny in 993, originated from liturgist Amalarius of Metz’s declaration in the ninth century. Inspired by a reading from 2 Maccabees, Odilo sought a dedicated day for the deceased.

In a folk tale, a shipwrecked pilgrim reported to Odilo that a hermit claimed to hear tormented souls from a flame-engulfed gorge. To honor them, Odilo instituted All Souls’ Day on November 2, emphasizing a “communion of saints.” Pope Sylvester II sanctioned the holiday in 1000, spreading its observance throughout the medieval world.

The Church Revitalized Paganism

The early Catholic Church significantly shaped Halloween, aligning it with ancient traditions. They sanctified the custom of honoring the dead on October 31, naming it All Hallows’ Eve before evolving into Halloween.

The Church revitalized pagan masquerades and parades through All Souls’ Day celebrations. Additionally, the introduction of soul cake baking and souling songs arguably laid the groundwork for contemporary trick-or-treating practices.