Neanderthals might have experienced a few very familiar diseases 50,000 years ago, which might have led to their extinction.

Three viruses that cause colds, cold sores, genital warts, and cancer were found in ancient Neanderthal DNA.

Ancient Human Spread

What’s more, ancient humans could have been the ones who began spreading these bugs, as per the researchers who recently distributed their work in the peer-reviewed journal “Viruses.”

The majority of experts on Neanderthals believe that the species went extinct for a variety of reasons, including human interactions, low fertility rates, and a changing climate. It probably wouldn’t have helped to recover from illnesses, especially unfamiliar ones from distant cousins.

“Competing with Another Species”

Marcelo Briones, one of the researchers who discovered the viruses, told Business Insider via email that poor health caused by “these types of infections can have a negative impact when you are competing with another species.”

Not only could these old infections add to how we might interpret Neanderthals’ downfall, but they could assist us with understanding more about the contemporary forms that still infect people today.

DNA Sequencing

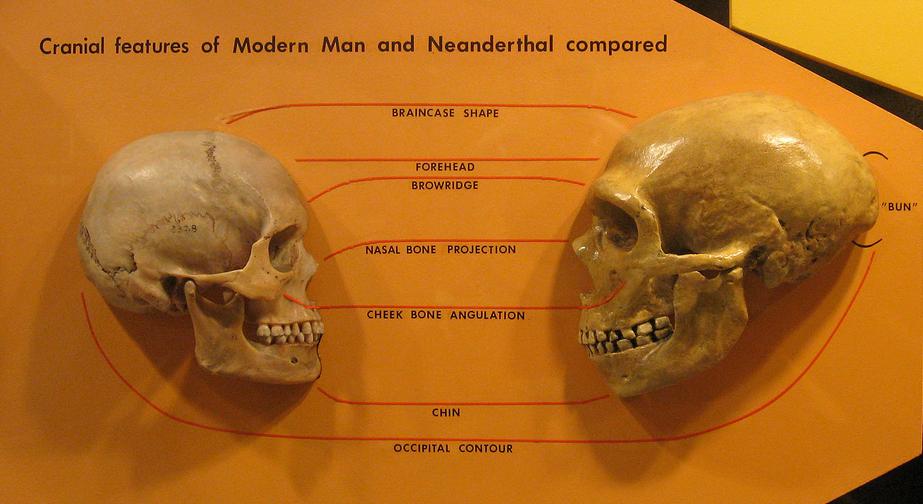

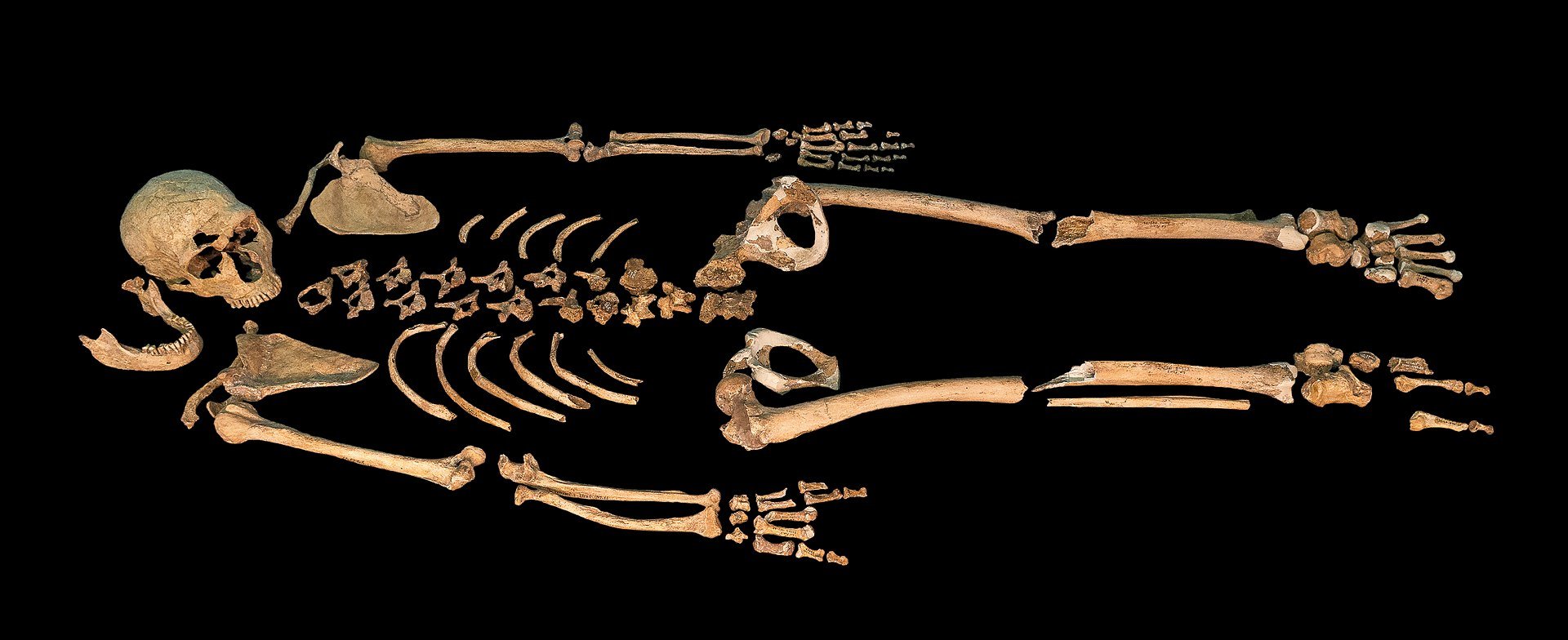

A small group of Neanderthals lived in Southern Siberia’s Chagyrskaya Cave approximately 54,000 years ago.

Briones and his colleagues looked for evidence of three viruses they thought might have contributed to the extinction of the Neanderthal species in the sequenced DNA data of two Neanderthals from the cave: an adult male and a boy. These were adenovirus, herpesvirus, and papillomavirus.

Inert Viruses

Herpesviruses can cause cold sores or genital warts, depending on the type. The adenovirus can cause respiratory infections like the common cold and the flu. The papillomavirus is linked to certain cancers, like cervical cancer.

This isn’t the first time scientists have seen inert (not infectious any longer) ancient human viruses. A 2021 report described the revelation of adenovirus in 31,600-year-old human teeth from Siberia.

Interbreeding

The adenovirus, herpesvirus, and papillomavirus found in this later review are almost 50,000 years of age, as per the researchers— 20,000 years older than the adenovirus tracked down in the Siberian teeth.

That is around the time a few specialists think that people and Neanderthals interbred, somewhere in the range of 60,000 and 50,000 years ago. As well as trading DNA, people and Neanderthals most likely passed around illnesses.

Immune Response

It’s not certain if recently introduced infections would have caused the same side effects in Neanderthals that they truly do in present-day people.

While contaminations probably prompted an immune response, it’s hard to tell how severe coming down with such sicknesses would have been, Briones said.

Neanderthals Fate

One 2016 review hypothesized interbreeding with Neanderthals might have helped people’s resistance to obscure illnesses. The Neanderthals however might have been less fortunate.

Briones stated, “A cold does not have to be fatal to decrease hunting efficiency or reproductive ability.”

Contribution to Modern Understanding

With an already small populace, becoming ill with new diseases could have impacted Neanderthals’ eradication around 40,000 years ago.

Understanding how these ancient diseases changed over tens of thousands of years could help us understand how they affect us today.

“Long-Lived Infections”

Some viruses remain in your body forever. “They have a huge impact on human health because they are long-lived infections,” said Sasha Tabachnikova, a PhD candidate examining herpesvirus at Yale School of Medicine. Recent research has connected Epstein-Barr — a sort of herpesvirus — with multiple sclerosis, for instance.

Although she was not a part of the paper, Tabachnikova is excited about the possibility of studying the evolution of an ancient virus since the Neanderthals. However, such research is probably a ways off.

Difficulties of Ancient DNA

Ancient DNA is difficult to work with. It deteriorates and breaks into short sections. The more drawn out a sequence of DNA is, the easier it is to distinguish.

“When the sequence is too short, you will find them everywhere, in all types of genomes,” according to Diyendo Massilani, an associate professor of genetics at Yale. That can prompt misinterpretations in the information.

Verifying Findings

Viruses already have DNA strands that are shorter than humans. Sally Wasef, a paleogenetics researcher at Queensland University of Technology, told New Scientist that this indicates that the methods used to study ancient human DNA might not apply to viruses.

Massilani likewise had a few concerns with how the scientists were deciphering the Ancient DNA. “They probably have a good idea,” he said, yet they need to change some of their strategies to fortify their outcomes.

Briones stated that he and his coworkers intend to conduct additional research to verify their findings.